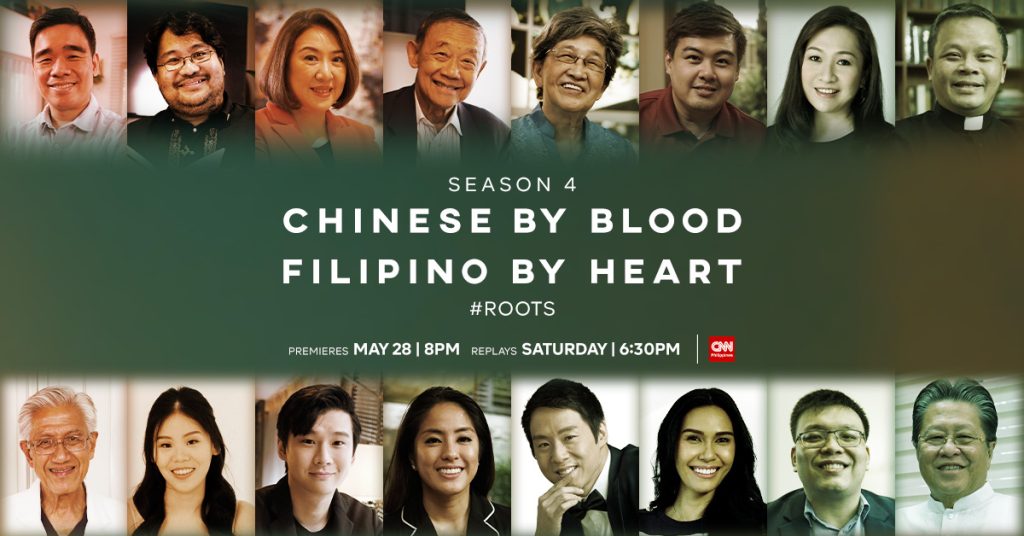

Although some food in Filipino cuisine has dubious origins or has been indigenized to the point of being unrecognizable by Filipinos, there is no doubt that real Chinese culinary items have carved out a place within Filipino cuisine.

Today, the best place in the Philippines to eat traditional Chinese culinary products like tikoy, hopia, Mami, siopao, and siomai is in Binondo. Binondo was built in 1594 as a Chinese village across the river from Manila’s walled city by Spanish Governor Dasmariñas. Despite a royal edict for the deportation of all Chinese, Damariñas recognized that the city of Manila was heavily dependent on Chinese services.

Certain Filipino recipes (pancit, adobo, lumpia) clearly demonstrate a history of Hokkien influence, whether through cooking methods (boiling, steaming, stir-frying) or ingredients (soy sauce, Chinese cabbage). However, according to Olivia Zapanta-Mir, co-owner of Manila Eatery in Colma, CA, it is the combination of ingredients native to the Philippines that were introduced by the Chinese that make Filipino cuisine what it is— a hybrid. This is not to diminish the Chinese influence on Filipino cuisine, but rather to acknowledge Chinese contributions.

This fusion of cooking techniques and ingredients demonstrates not just the diversity of Filipino cuisine, but also the resourcefulness of those who prepare it. Hokkien cooking techniques coupled with Chinese and Filipino ingredients have been used for generations. Hokkien cuisine has evolved over the last several centuries as it has become indigenized throughout Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, etc.). During this progression, the composition of several foods was changed to accommodate the native palate. As a result, by combining Chinese cooking skills and ingredients with the growth and creation of culinary dishes. Some classic Hokkien foods have lost their Chinese identity on the surface and have been substituted with a purportedly Filipino one throughout the decades.

1. Pancit

While the Filipinos may have indigenized pancit, such as pancit palabok or pancit malabon, the symbolism associated with the consumption of the noodles was not lost in translation by them. Although pancit developed from Hokkien cuisine to a Filipino dish, the noodles themselves are still consumed during festive events and represent longevity. Moreover, the noodles are still kept uncut since cutting them represents the shortening of one’s life, which is considered bad luck in Chinese customs.

2. Tikoy

Tikoy is a classic Chinese sticky rice cake. Tikoy is a Filipino name originating from the Hokkien term tee kueh, which means “sweet cake.” While the exact date when tikoy was introduced into Filipino food and culture is unknown, it is largely accepted across the Philippines that tikoy rose to prominence around the early twentieth century thanks to Chua Chiu Hong.

Chua opened a modest store along Ongpin Street in Manila’s Chinatown in 1912. This kiosk specialized in traditional Chinese cuisine. After more than a century, this formerly modest shop has grown into the now globally known Eng Bee Tin Chinese Deli, which has multiple locations around the Philippines. While tikoy may be eaten at any time of year, it is most commonly consumed during Chinese New Year in the Philippines and China. Tikoy is a popular gift item among the Chinese during the New Year because of its characteristic round money-like form, which represents riches. As a result, giving tikoy as a gift represents bestowing riches on the recipient.

A more recent attempt by the Chinese in the Philippines to promote tikoy to Filipino consumers has succeeded. This Chinese marketing brilliance offers tikoy varieties tailored to Filipino preferences, such as ube, pandan, and even strawberry. The traditional Chinese New Year rice cake has become a vital component of Filipino cuisine, thanks to the concept of good luck and fortune paired with tastes tailored to the Filipino palate.

3. Hopia

Hopia is another pastry that has become a staple of Filipino cuisine. Hopia, a spherical, bean-filled pastry, can be presented as a gift to friends and family on special occasions or consumed on any day. Hopia, like tikoy, was brought to the Philippines by Hokkien immigrants from Fujian, China. While tikoy is mainly connected with the Lunar New Year, hopia may be traced back to the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as the Mooncake Festival, which occurs on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month. The mooncake, like tikoy, was meant to signify a cohesive family since mooncakes were given as presents to each other. However, the development of hopia may have been a method for overseas Chinese to make the mooncake a year-round confection rather than a seasonal treat. Hopia has become a more marketable commodity among Filipinos thanks to the Chinese. It became a convenient snack item due to its price, size, and relative ease of eating.

Hopia is available in a number of flavors, including mung bean, red bean, winter melon, ube, buko pandan (young coconut flavored with pandanus tree leaves), and langka (jackfruit). The Chinese mooncake inspired the more classic hopia tastes of mung bean and winter melon. However, according to Gerry Chua of Eng Bee Tin Chinese Deli, the traditional hopia mongo (mung bean) and hopia ube (purple yam) types are the most popular among Filipinos.

Ironically, the genesis of ube-flavored hopia is one of desperation. Chua devised this flavor as his family company began to crumble. Chua mastered the skill of ube manufacturing and experimented with various methods of putting ube into hopia to resuscitate the family company. Chua’s desperate creativity has resulted in ube-flavored hopia being a popular hopia flavor among Filipinos. Amazingly, ube-flavored hopia was able to combine the best of both Chinese and Filipino cultures.

4. Mami

Mami is the classic chicken noodle soup among Filipinos. According to Ian Ma, Ma Mon Luk’s great-grandnephew, the name Mami is a mix of the term mi, which translates to noodles, and the family surname Ma. However, Ma in Mami is a contraction of the Hokkien term maq, which translates to meat. Mi may also refer to two types of noodles: Chinese wheat noodles and Chinese egg noodles. Miki, or Chinese wheat noodles, resemble fettuccine or circular spaghetti in appearance.

Unlike tikoy and hopia, which have traditional Chinese superstitions associated with them, Filipinos embraced Mami largely as a comfort dish. Mami became popular owing to its low cost paired with the fact that it was a quick method to satisfy one’s appetite. When Ma initially started selling his chicken noodle soup on the streets of Chinatown, the bulk of his customers were students, office employees, and regular walkers searching for a cheap, quick, and full midday snack.

Almost a century later, this Cantonese-style chicken noodle soup has become an iconic staple in Filipino cuisine, offering students and working-class people a cheap, fast, and full lunch. Even among the diasporic Filipino population in the United States, mami is never far away, since quick variants are accessible at Asian and modern grocery shops.

There are far more than these four uniquely Chinese foods in Filipino cuisine. Except for tikoy, all of the things described have become comfort food for Filipinos. Check out our article with Binondo restaurant suggestions to try the food mentioned and experience the deep history behind it.